In the trademark laws and regulations and judicial practices of various jurisdictions, there are two controversial issues in the field of well-known trademarks:

1、 Are only trademarks that have reached the level of well-knownness eligible for cross-Class protection? If a trademark has a certain degree of reputation but is not yet well-known, can its protection scope be extended to some related but non-similar goods and services?

2、 If a trademark is well-known or has a certain degree of reputation in country A, but has not been registered or used in country B, can it be protected in country B?

Before we analyze the above two questions in depth, let us put aside the existing laws of any specific country and re-examine what the essence of trademarks is, why trademarks should be protected, and what is the relationship between trademarks and the scope of protection they deserve from the perspective of spirit of laws?

The essence of a trademark is an identification that enables the relevant public to distinguish the source of goods/services.

There are two purposes for trademark protection:

1) Public rights: avoid confusion and misunderstanding among consumers and protect the interests of the public;

2) Private rights: avoid damage to the reputation and economy of the trademark owner and protect the interests of the business operator.

Based on the above two premises, I believe that the core role of trademark law and related systems is to ensure that trademarks obtain a scope of protection that matches their distinctiveness and reputation.

Breaking down this sentence, there are several key points:

Distinctiveness: As the innate, inherent and inherent characteristics of a trademark, it is a common attribute of all forms of trademarks (regardless of text, graphics, three-dimensional, sound, smell, location, etc.), and is the decisive factor in distinguishing trademarks from non-trademark signs. The presence or absence of distinctiveness determines whether the trademark right is established, and the strength of distinctiveness affects the scope of protection of the trademark right. For example, although "Great Wall Wine" is famous, because "Great Wall" is a scenic spot and is used as a trademark by different companies in many fields, its distinctiveness is relatively weak. Great Wall wine cannot prevent other companies from using Great Wall lubricants or Great Wall motors, so the actual scope of protection is limited due to its distinctiveness;

Reputation: As an external feature of a trademark formed through the use of operators, media dissemination, and word-of-mouth of consumers, it carries the goodwill of the enterprise, determines the value of the trademark, and affects the degree of confusion, misrecognition, and association that consumers may have. The higher the reputation of a trademark, the greater its influence, the deeper the impression of the relevant public, and the higher the possibility of misrecognition when identical or similar trademarks appear. Therefore, the level of reputation affects the scope of protection of the trademark right;

The variables that have a decisive influence on the scope of protection are only "distinctiveness" and "reputation", and there is no mention of "whether or not registered " or " scope of registration ". The reason is that registration is not the essential value of a trademark, but a tool artificially created by the trademark legal system to more conveniently and efficiently carry out the protection and management of trademarks, and to facilitate other social entities to search trademarks. To make an analogy: just like a luminous gem, in order to better manage and protect it, people take photos of the gem and put labels on the photos to record the number, origin, owner, material characteristics, etc. This labeled photo is not the same as the gem itself. The photo may deviate from the actual object, and the record may be inaccurate and incomplete, just like the trademark registration is likely to be not 100% consistent with the trademark in actual use (trademark form, scope, etc.). Therefore, when the gem is damaged and the degree and scope of the damage need to be calculated, we should focus on the characteristics, quality, luminous intensity, value, etc. of the original gem, rather than just looking at the labeled photo;

The variables that have a decisive influence on the scope of protection are only "distinctiveness" and "reputation", and there is no mention of " whether or not used " or " scope/extent of use ", because the act of actively using a trademark by an operator is only one of the ways for a trademark to gain reputation. In addition, there are the following ways: 1) Nicknames given to a brand by consumers or the relevant public may be widely circulated in the market. Although they are not used by the operator, the nicknames have assumed the essential function of a trademark, that is, to distinguish the source of goods and services. If they are not protected, it will not only cause confusion among consumers, but also damage the interests of the operator. Therefore, "use" is not a necessary variable; 2) Although a trademark is only used in its home country, its reputation extends overseas, especially to neighboring countries. Consumers in neighboring countries have heard of it or even expected it. If they see an identical brand on the market, they will be mistaken. Neighboring countries should protect such trademark which is not used but have certain reputation in these countries. Therefore, "scope of use" is not equivalent to "scope of protection";

Another key wordin "protection scope matching its distinctiveness and fame" is “matching”, because neither "distinctiveness" nor "fame" has only two options of "yes/no", but an interval value. For example, the interval from 0 to 1 includes 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1, and can even be further subdivided, from 0 to 0.1, there are 0.01, 0.02, etc. If the trademark system only considers the two extreme states of "well-known" (i.e. 1) and "not well-known" (i.e. 0), only well-known trademarks can be protected over dissimilar goods/services, and not well-known trademarks can only be protected over similar goods/services, which means that the protection scope enjoyed by trademarks with a reputation of 0.9 and 0.1 is the same, which is obviously unscientific and unreasonable. Only by fully understanding the concept of "interval" that is more in line with actual reality and avoiding falling into the two-level state of "yes/no" can a more matching protection scope be determined. The more sophisticated and scientific the legal system designs the "matching", the more fair, just and reasonable it will be, and the more conducive it will be to a healthy and orderly market operating environment and a virtuous cycle. On the contrary, if the matching mechanism is rough and the logic has loopholes, it is very likely that a large number of trademarks in the middle of the interval (such as 0.5, 0.6, 0.7) cannot obtain the protection they deserve. The consequences of this will not only damage the interests of the owners of these trademarks, but will also confuse and mislead the relevant public, disrupt market order, and provide opportunities for "dishonesty" and "free riding" to exploit loopholes. At the same time, it will also produce a negative demonstration effect of high rights protection costs and low plagiarism costs, leading to negative social trends.

There has never been any perfect law or system in the world. With the development of society, the law always needs to be improved. Amending the law is not like fixing a bug. We cannot rob Peter to repair Paul, nor can we treat the symptoms without addressing the root cause. Instead, we should see the essence of the problem and the core of the legal spirit and then clarify the direction of improvement. I believe that the direction of improvement of trademark law and related systems is to improve the above-mentioned "matching mechanism" to achieve a more refined effect, so that trademarks can obtain a protection scope that matches their distinctiveness and reputation. The "protection scope" mentioned here has two aspects, one is the scope of goods/services (industry field), and the other is the geographical scope (countries and regions). Below we use several sets of charts to more intuitively verify the rationality of the above logic, and also provide a mathematical expression as a reference for system design:

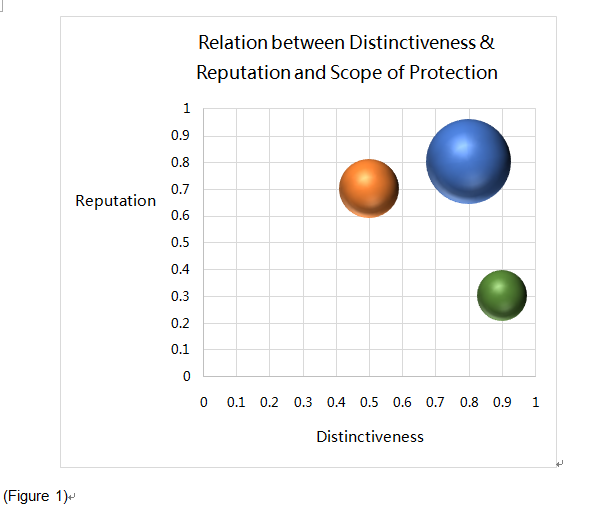

The meanings of the coordinate axes and spheres in Figure 1 are as follows:

- The horizontal axis represents the degree of trademark distinctiveness, 0 means no distinctiveness at all (e.g., generic or descriptive, “car” used on cars, “delicious” used on food), 0.1 to 0.2 means weak distinctiveness (e.g., suggestive, “Rain Dance” used on car wax), 0.3 to 0.4 means medium-weak distinctiveness (e.g., surname, “Williams” used on pens), 0.5 to 0.6 means medium distinctiveness (e.g., arbitrary, “Apple” used on mobile phones), 0.7 to 0.8 means medium-strong distinctiveness (e.g., new words formed by combining meaningful words or abbreviations, “Microsoft ” used on software), and 0.9 to 1 means strong distinctiveness (e.g., fanciful trademarks IKEA, EXXON, etc.);

- The vertical axis represents the range of trademark awareness, 0 represents no awareness (e.g. a new brand that has not yet been put into the market for use and promotion, and the relevant public is not aware of it), 0.1 to 0.2 represents low awareness (e.g. an initial brand that has just started to sell in a certain market, and a small number of relevant public are aware of it), 0.3 to 0.4 represents medium-low awareness (e.g. a brand that has been in business for several years, although the market share is not high, but has a place in the main business channels and media channels of the industry, and some relevant public are aware of it and have formed word-of-mouth reputation), 0.5 to 0.6 represents medium awareness (e.g. brands that can enter the industry rankings, although the ranking is not high, but have also won some honorary awards, have publicity and advertisements, and have a certain reputation and influence), 0.7 to 0.8 represents medium-high awareness (e.g. a brand that ranks at the top of the industry rankings, has many honorary awards, and the relevant public has heard of this brand when it is mentioned, and has a high reputation and influence), 0.9 to 1 represents high awareness (i.e. well-known) (e.g. Coca Cola, Google);

- Each sphere represents a trademark. The size of the sphere represents the scope of protection of the trademark, which is determined based on the two variables of the trademark's distinctiveness (a) and reputation (b). Considering that reputation has a greater impact on the scope of protection, a certain weight is added, and the final resultshould be less than or equal to 45.

For example, f( a,b ) = 3 0* a * b 3 + 10* a * b+5 * a.

The trademark represented by the orange sphere: f(0.5,0.7), protection scope=11

The trademark represented by the green sphere: f(0.9,0.3), protection range=8

The trademark represented by the blue sphere: f(0.8,0.8), protection scope=23

Of course, the resulting value of the protection scope cannot directly equal to the number of Classes to be protected, because the concepts of trademark distinctiveness, reputation, and the correlation between different Classes of goods/services are relatively subjective and difficult to quantify accurately. The above formula only provides an analysis method for reference.

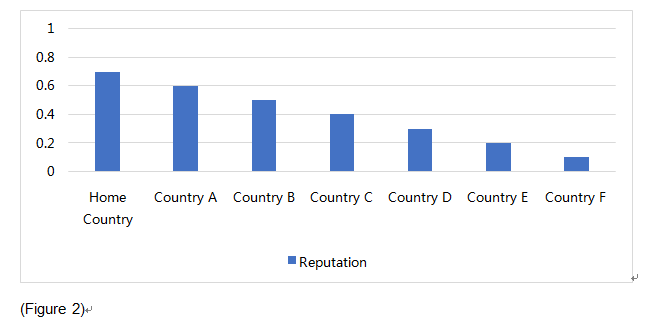

In addition, "reputation" should be broken down into different countries/regions because when evaluating the reputation of a trademark, it cannot be simply divided into domestic and foreign. There are more than 200 countries and regions in the world, and the reputation of the same trademark in different countries/regions outside its home country may also vary.

For example, the reputation of an American brand may be 0.7 in the United States, 0.6 in Canada, 0.5 in New Zealand, and 0.3 in Thailand. The influencing factors include the brand's own activity in these countries, as well as the geographical relationship between countries, industry development status, cross border travel &trade exchanges between countries, language, culture, etc.

Finally, let us return to the two questions mentioned at the beginning of this article:

Question 1: Are only trademarks that have reached a well-known level eligible for cross-Class protection? If a trademark has a certain degree of reputation but is not yet well-known, can its protection scope be extended to some related but non-similar goods and services?

According to the above-mentioned "matching" principle and logic, such trademarks should also enjoy a scope of protection that matches their distinctiveness and reputation, that is, extended to some related but non-similar goods/services.

In some countries /regions (such as the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Australia), there are not only well-known trademark, but also a concept of "trademark with certain reputation" in their trademark systems. This concept covers some trademarks in the reputation range (such as 0.3~0.9), allowing trademark examiners or judges to grant certain degree of protection outside the original Class at their discretion in specific cases based on the evidence submitted by the parties.

Some people may ask why bother so much? If you want to protect a wider scope, can't you just add a few more Classes when registering the mark? Anyway, the trademark application fee is not expensive, just like spending money to purchase land. If you choose too few Classes at the beginning, you can only bear the consequences yourself. Such arguments sounds reasonable but are indeed wrong from the beginning. It is like when a person's wallet is stolen, instead of punishing the thief, we blame the unlucky person who was stolen, "Why don't you put your wallet in a zipper pocket?" "Why don't you tie your wallet to a chain and hang it around your neck? Anyway, the chain is not expensive." A good legal system should increase the cost of doing evil, rather than increasing the burden that honest people have tobear to prevent being hurt by evil. In addition, the trademark registration system should adhere to the core principle of "trademark is used or intended to be used to distinguish goods or services", which is also a recognized principle in various countries internationally. Some countries require the submission of a use statement or evidence of use when applying for a trademark or before the registration is approved, and some countries stipulate that a registered trademark can be canceled if it has not been used for three or five years after registration. These rules are all based on the principle of "trademark is used or intended to be usedto distinguish goods or services". The legal system cannot be self-contradictory. On the one hand, it requires applicants to strictly limit their choice of Classes to only “for the purpose of use”, while on the other hand, punishing parties who abide by this principle when exercising their rights.

Some people may say that enterprises can use trademarks in other Classes to diversify their business. Shouldn’t they allow others to use the Classes they don’t use? This view is even more absurd than the requirement of “tying the wallet to a chain around your neck” mentioned above. It is like a thief saying to the person who was stolen, “Since you only used your money to buy vegetables and didn’t use it on fruits, why can’t I use your money to buy fruits?” Starbucks trademark is used on coffee (Class 30) but not on mouthwash (Class 3). If someone asks, “Since Starbucks doesn’t use its trademark on mouthwash, can’t others use the Starbucks brand to sell mouthwash?” Since the distinctiveness and reputation of the Starbucks trademark are very high, the corresponding protection scope should also be relatively large. Should the scope include “mouthwash”? It would be obvious that when consumers see "Starbucks" brand mouthwash on the market, they will think of Starbucks, mistakenly believing that Starbucks has extended its business scope to mouthwash, andwill guess that it may be a coffee-flavored mouthwash, thus mistaking the actual source of the product. Therefore, the matching protection scope here should include mouthwash.

Therefore, the scope of protection that a trademark should enjoy should not be limited by the “scope of registration” or “scope of use”, but should be defined according to the distinctiveness and reputation of the trademark. Even if it is not a well-known trademark, as long as the trademark has a certain degree of reputation, it should also obtain a corresponding degree of extended protection scope beyond the original Class.

Question 2: If a trademark is well-known or has a certain degree of reputation in country A, but is not registered or used in country B, can it be protected in country B?

Nowadays, Internet media covers the whole world, cross-border information exchange and sharing are almost free and instantaneous, and cross-border travel is developed and prosperous. If consumers in country B also have a certain understanding of the trademark, that is, the trademark is not used in country B but is well-known, then the trademark also plays the essential function of a trademark in country B. If the protection of the trademark is limited to country A where it is used, and does not include country B where it is not used but has certain reputation, it is actually contrary to the spirit of laws, because this will not only cause confusion and misunderstanding among consumers in country B, but also damage the interests of the trademark owner.

At this point, some people may bring up the old rule that "trademarks are territorial rights". First of all, we should realize that this principle was proposed long before the birth of the Internet. At that time, information was relatively closed, media was relatively monopolized and concentrated, and transportation was not yet developed. It was reasonable to define the scope based on the jurisdiction of registration and use of trademarks. However, the situation is very different now. Information is transparent and shared, media is extremely decentralized (we media, fan economy), and transportation is convenient and economical. Therefore, the "territorial" is no longer "territorial" of "registration" or "use", but the "territorial" of "reputation". This interpretation of this principle is more in line with the needs of trademark protection in the context of modern society. Therefore, if a trademark is well-known or has a certain degree of reputation in country A, even if it is not registered or used in country B, it can obtain a matching protection scope in country B based on the distinctiveness of the trademark and its reputation in country B.

Although judging and calculating the "distinctiveness" and "reputation" of a trademark is more difficult than judging and calculating the "scope of registration" and "scope of use " of a trademark, there are more subjective factors and it is easy for inconsistent standards to occur, but as mentioned above, the two factors of "distinctiveness" and "reputation" truly correspond to the essence and value of the trademark. I believe that with the rapid development of science and technology, it may be possible to use AI models to calculate the "distinctiveness" of a trademark in the future, and use Internet big data and AI models to calculate the reputation of a trademark in a certain country/region.

Hope the progress of law and technology can truly bring more fair, just, healthy and orderly and orderly development to human society.

Follow us