Much progress has been made in recent years when it comes to protecting name and image ights, and to fighting against bad-faith registrations in China.

The right of publicity usually refers to the right of a person to control the commercial use of his or her name, image and other aspects of identity.

In China, publicity and image rights are protected under Articles 99 and 100 of the General Principle of Civil Law (Articles 109 and 110 of the amended General Principle of Civil Law, which is due to be implemented on October 1 2017). These provisions prohibit a third party from making commercial use of a person’s name or image without consent.

According to Article 99, individuals enjoy rights over their personal names and are entitled to determine, use or change these in accordance with relevant provisions. Article 100 states that individuals enjoy rights over their image and prohibits the use of an image for profit without the subject’s consent.

Similar provisions can be found in the Trademark Law. According to Article 32, an application to register a trademark must not prejudice the prior right of another person or be used to pre-emptively register a trademark which another person has used and which has garnered a certain reputation. This prior right covers personal names, images and trade names, as well as copyright and design patents.

The China Trademark Office (CTMO) will not investigate whether a trademark infringes a personal name right during examination unless it contains the name of a living political figure – although such applications may be rejected for having an unhealthy influence on society, under Article 10.1(8) of the Trademark Law. Any interested person can file an opposition against a preliminarily published trademark or initiate an invalidation action against a registered mark if he or she believes that it infringes his or her name right.

Name rights cover given names, pen names, stage names and nicknames. Only a natural living person can claim a personal name right under Article 32. In such cases, the disputed trademark should be identical to his or her name, or be a well-established translation of it.

The name rights set out in the Trademark Law are designed to protect not only human dignity, but also economic interests. The law recognises that the use and registration of a mark which is similar or identical to a person’s name could mislead consumers into believing that there is a direct relationship between that person and the trademark (eg, endorsement or permission). Thus, the subject’s reputation is a crucial factor when it comes to determining whether a trademark infringes another’s name right.

In December 2016 the Supreme People's Court issued a decision in the Michael Jordan case, which attracted a great deal of attention.

Chinese sportswear company Qiaodan Sports registered ‘乔丹’ for “machines for physical exercises, roller skates, etc” in Class 28.

US sports personality Michael Jordan claimed that this infringed his name right. The other side – and some experts – countered that Jordan's full name is Michael Jeffrey Jordan. The Supreme People's Court finally ruled in favour of Jordan, supporting his name right claim based on the Chinese transliteration of part of his name.

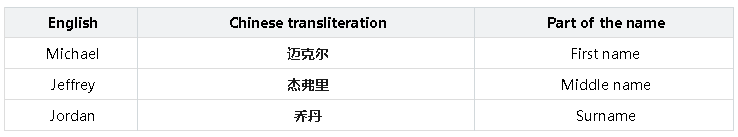

Below are Chinese transliterations for each part of Jordan's name.

The court considered that in certain circumstances the relevant public is more familiar with parts or versions of an individual's name (eg, a nickname or a stage name) than the full name.

Further, the relevant public in China is often accustomed to referring to foreigners by the Chinese translation or transliteration of their surname, rather than their full name. This practice should be taken into consideration when deciding whether a foreigner enjoys name rights over the translation or transliteration of part of his or her name.

In the case of Jordan, from 1984 to 2010 (before registration of the disputed mark), ‘乔丹’ was the most common appellation for him in the Chinese media.

In addition, the court held that a trademark’s function is to distinguish the goods or services of one undertaking from those of others – the mark should thus be considered together with the business or claimed goods or services that it denotes. While ‘Jordan’ is indeed a general surname in the United States, when used in relation to sports and basketball in particular (ie, the goods designated by the disputed mark), it suggests a direct link with Jordan. Further, it was demonstrated that ‘乔丹’ has been widely known for many years as a designation for Jordan among the relevant Chinese public in this field. Thus, the court concluded that Jordan enjoys name rights over the Chinese transliteration of ‘Jordan’.

Figure 1: Qiaodan Sports’ registered image mark

Qiaodan Sports also registered the trademark QIAODAN. Jordan’s claim for a name right over this mark was not established, because it was more difficult to prove a stable link between QIAODAN and ‘Michael Jordan’. While QIAODAN could be considered the Chinese pinyin of ‘乔丹’, this is not the sole correspondence – a number of Chinese characters can be pronounced as ‘qiaodan’, since there are four tones in Chinese.

Protection for name rights has improved considerably since the issuance of the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of the Administration of Trademark Examination, which were implemented on March 1 2017 and which state as follows:

Article 5: If the signs contain names of public figures in political, economy, culture, and religious areas, the signs could be identified as having unhealthy influence by the People’s Court;

Article 20: If the interested party claims that the trademark infringes his or her name right, if the relevant public considers that the trademark refers to the natural person and it is easy to mislead the consumers to think that the goods bearing the trademark have been authorized by the natural person or has a specific connection with the natural person, the People’s Court shall consider that the trademark infringes the natural person’s name right.

If the concerned party claimed name right for the pen name, stage name, or translation/transliteration of his or her name, if this specific name has obtained certain reputation which established stable imprints with the natural person, and the relevant public recognize the natural person with this special name, the People’s Court shall support their claim.

According to this, if a name enjoys a certain reputation and is linked to a natural person in the minds of the public, then a prior name right claim can be supported by a court.

According to the examination guidance issued by the CTMO and the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board, it is not possible to register the image of another person as a trademark without that person’s authorisation.

The CTMO is much stricter when examining trademarks which contain images of people than it is for those including names. Applications must include an original statement from the subject authorising the applicant to use his or her image; otherwise, the mark will be rejected for registration.

Trademarks do occasionally use computer-generated images and an examiner may find it impossible to confirm whether these are identical or similar to portraits of an individual. If an examiner approves such an application, the subject of the image may subsequently file an opposition or an invalidation action.

Similar to name rights, rights in an image can be claimed only by a living natural person. The disputed trademark should be identical or similar to that person’s portrait – that is, it should reflect the main image which identifies this natural person.

Returning to Michael Jordan, Jordan also fought against the Chinese company’s registration of an image (see Figure 1) on the basis of his portrait rights, but the court rejected his claim. It reasoned that the figure was displayed in silhouette only, with no specific facial characteristics. Thus, it would be unlikely for the relevant public to recognise the figure as that of Jordan.

Figure 2: Disputed image of Usain Bolt

In another case, famous Jamaican athlete Usain Bolt filed an opposition against a distinctive image mark (see Figure 2). The CTMO supported Bolt’s claim and reasoned that as an Olympic champion, he is a famous athlete among the Chinese public and his iconic action (see Figure 3) is also familiar to Chinese consumers. It found that the disputed mark was similar to Bolt’s action with regard to the main features and overall appearance.

Figure 3: Photograph of Bolt's signature celebratory move

From these two cases, it can be seen that the specific facial appearance in an image is crucial when it comes to determining whether it infringes a person’s rights over his or her portrait. In Jordan’s case, the image could refer to any basketball player. However, in Bolt’s case, the trademark clearly indicated his iconic gesture, his yellow sport shirt and his facial appearance.

Much progress has been made when it comes to protecting an individual’s rights in his or her name and image, and in fighting against bad-faith registrations in China. Adapting the skills and strategies used in each specific case, and combining different grounds, should lead to many more successful outcomes in such cases.

Follow us